To Accept That There Are No Choices Left

echoes in the wake of Asia Suler's "A glass of water"

This letter was originally scheduled for publication on May 12th: Mother’s Day. In the end, I did not publish anything on Mother’s Day at all. When intersected with loss, the oddest days begin to take on too much weight.

Please note: what follows is a deeply personal exploration of details around death and the grief encircling it. If you are newly postpartum or in a tender season in your own life, it may be wise to avoid reading at the present time.

In honor of my mother.

In honor of all mothers who are grieved.

In honor of all mothers who grieve.

On the last day of March,

(writer at Mothering Depth) published a piece on the myriad small choices available to us, particularly when mothering forces us to face the choices that are no longer available.I can’t get more sleep, but I can drink a glass of water.

I cannot escape for the day into the woods, but I can choose to focus on the sound of the birds when my daughter nurses at dawn.

I won’t be able to plant the flower garden this year, but I can touch the cherry blossoms so the petals fall down on us like rain.

I cannot be anywhere else, but I can be here now.

Her words were for mothers. For the nurturers of life in its seedling form, for the days when all we can do is shelter in place as an offering to the future for our little ones and ourselves. When I read her words, however, I didn’t think of the many night wakings for nursing even now, or the long hours spent pacing the floor when my babe was tiny. I didn’t think of my own experience of motherhood at all.

Instead I thought of my mother.

Perhaps it’s that I was bleeding when I read Asia’s words, sinking into the monthly stripping-to-the-bone that my menstrual cycle has become.

Perhaps it’s simply due to the dreams that were carrying up images and conversations from the depths of old memory, bringing the keys to release locked-away griefs. For months now, morning rising has also meant carrying with me from my bed an invisible shade of sadness, clinging from the night’s inner wanderings.

And perhaps that is why when I read Asia Suler’s “A glass of water” I thought of my mother.

In thirteen days from today her body will have been dead for two years.

There is a matter-of-fact part of me that has carried on with the perceivable functions of life and accepted the fact of her absence. (I find myself within the first stage of Jean Piaget’s theory of cognitive development: I am a child caught in the moment before understanding object permanence. The object, once removed, is believed to be no more. The child wails.)

There is a part of me that is still waiting for her return. (Again, Piaget: the child has developed object permanence and will continue to wait and watch and reach in the direction which the object has disappeared, expectant of its return).

She was just there, at that table, in that place; I can hear her laughing up the hillside; she scolded you for that dirty joke just two moments ago; she’s going to be back from doing home visits in several hours; where is she now? up in the garden. Up in her garden.

In my memories she is vibrant. Laughing. Alive.

In my dreams, she is always on her deathbed.

//

As a child, I was preoccupied with death. I felt keenly aware of the fact that—while I was greeting my life—unnamed and innumerable people were departing theirs. I re-read death scenes in novels again and again, browsed encyclopedic entries on wars and large-scale destruction, and kept a multitude of tiny invented rituals meant to ward off personal loss, despite audaciously considering myself an unsuperstitious human (as if).

This thread continued past childhood. In my late teens and early twenties I lingered over the English translation of Intimate Death: What the Dying Teach Us by hospice doctor Marie de Hennezel, The Year of Magical Thinking by Didion, and The Summer of the Great Grandmother and A Severed Wasp by Madeleine L’Engle. In clinical training and academic study, I spent extra time over ethics around palliative care for unborn babies and newborns with terminal conditions. I sat for hours in dark bedrooms with miscarrying mothers, learning the rhythms of labor when what is intended to culminate in ecstasy has already been transmuted to grief.

In one particular instance, one where I collected footprints from a babe born at just twelve weeks gestation, the baby and placental sac had been born into a small stainless steel kitchen bowl before we arrived at the house. Cultural tradition in that community meant leaving the baby, born too early to determine sex with absolute uncertainty, unnamed. After seeing those tiny footprints, after wrapping their little one in a cotton handkerchief and tucking her into a small cigar box for burial, they decided to give her a name.

I still viscerally remember those tiny feet in my too-large fingers, that tiny body cradled in my hand as I knelt on the bedroom linoleum. I remember the dull thud of soil-calloused feet travelling across the farmhouse floor, and the murmured recounting of how the birth had unfolded, a recounting made without tears.

I don’t remember the name they gave the baby.

//

My mother, a midwife, opened the door for me to travel alongside her into the realm of loss many, many times. In the span of fifteen years she attended over a thousand births, caring for mothers through their successive pregnancies with a rarely matched balance of compassion, understanding, and practicality.

She also attended funerals. A husband killed in a farming accident, babies dead in the first weeks of life from lethal genetic conditions. Children passed too early after unexpected catastrophe, sometimes children her hands had been the first to touch.

It was my mother, in her patient kindness and her willingness to face her own grief, who taught me that to live is to inhabit one’s own uniquely personal boneyard. She was not afraid to mourn, she was not afraid to confront her own weakness. I watched her grieve without shame, heard her wrestle vocally with the anguish of What Ifs. There were births she witnessed that seared into her soul. There were decisions she made that she reckoned with ever after.

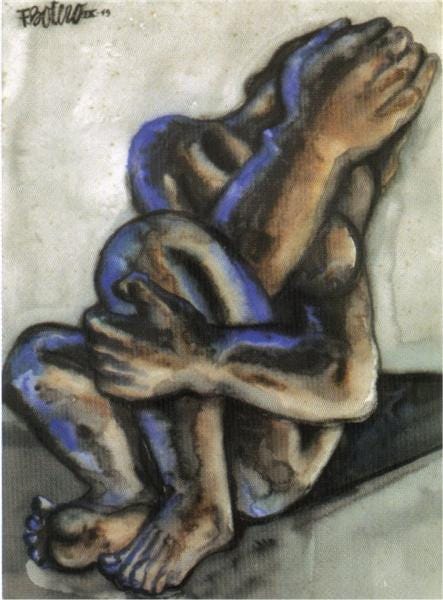

And after years of watching her walking the overlapping spheres of birth and death, I watched her in her dying, turning over her anguish in leaving her family so soon. I watched the choices, one by one, be stripped from her.

Her ability to attend births went first. Despite her ongoing enthusiasm and deep love for her clients, her body could no longer hold the fast pace of clinical work. First she let go of clinic days. Then, the option of attending even a few births a month, reserved for clients and dear friends, became an option no more.

After the births went her beloved garden. Pain took her away her mobility. She began to sit indoors, often with ice packs over the most painful areas. Direct sunlight became excruciating. Headaches increased. Her delight in her family’s explosive laughter morphed into flinching if our joy became too loud.

In August of 2021, the staircase became torture. Her world collapsed from the walls of our house to the four walls of her bedroom. Showers and baths were replaced by sponge-baths, a commode became part of the furniture we used as seating in her room. We carried our dinners night after night up to her bedroom. For half a year we shared meals in a circle on her carpeted floor.

Then went eating. The foods she loved to eat became unchewable. Her vision started to blur. Getting up to use the commode became impossible. We leaned on puddings and smoothies to get nutrition into her beloved mother-body, a body fast becoming translucent.

The last to go before her breath was her voice. Forty-nine years of a voice that anchored us all in song, stilled.

She could no longer sing to us, so we sang to her, fighting to let music emerge past our tears as she lay quietly with her eyes closed and a foot in both worlds.

Here is this, an offering, and an offering, and another offering—you have given us everything and this is all we have left to give.

In the beginning, the Word.

In the end, silence.

//

What I have gathered here are simple, physical facts. Anything abstract or poetic in them is accidental, the byproduct of an endless inner circling around a single external event. Around the nexus of many events, threaded and anchored in the body of a woman who birthed herself first as mother when she gave birth to me, a child she did not mean to conceive.

To relate these facts of her dying, to read them over, is to shape into words a physical pain.

“I keep thinking there must be something else I have to give.”

My children still need me, don’t they?

It can’t possibly end so soon, does it?

But it ended.

It ended.

We still need you.

And gone.

The skeletal fragments of her death are scattered through my own boneyard. A collection of symptoms, a slow progression turned to rolling stone, shedding moss, ended in a shadow of a grave marker yet to be given. It’s easy to say “There’s nothing that could have been done.” It’s much harder to live in the shadow of the question, “But could we have done something?”

I don’t know the answer to that question. I dream with it, I wake to it. The What Ifs are almost more terrifying than the Known. I find myself veering far away from new research on sarcomas, circumventing the inevitable suffocating plunge into “What if this might have been her doorway back into life? What if we had known about that treatment option earlier?” But always I go back to both the research and the question. Always I am left feeling as if I cannot breathe.

Almost a year after she died I listened to an interview in which the cells of the body were described as emitting light. The interviewee described how watching cancer on a microscopic level was to watch the light of the cells literally be snuffed out. I stopped the interview midsentence and never went back to it.

All I could think was this: from the very moment of re-diagnosis I should have driven across the miles that separated our bodies. I should have climbed into her bed and wrapped my arms around her, to hold her and hold her and hold her. Could the light of my cells have cut through the fast-growing tumors? Could I have reached the core of her being, pushing past the myriad shadows if I had clung to her, skin to skin? Could I have anchored her Being into her Body?

Could we have used the weight of our flesh and bones to keep her here?

//

There is a poem by Madeleine L’Engle, titled “Lines After M.B.’s Funeral”. I re-read it often.

There’s a hole in the world.

I'm afraid I may fall through.

Someone has died

Was

Has gone

Is where?

Will be

Is

How?

This is neither the first

Now the only time that space has opened.

We are riddled with death

Like a sieve.

The dark holes are as multitudinous

As the stars in the galaxies,

As open to the cold blasts of wind.

If we fell through

What would we find?

Show me

Let me look through this new empty place

To where

The wind comes from

And the light begins.

What happens, I wonder, when there is no place to go?

When we reach for the warmth of a beloved body and instead find our fingers reaching through the void in the world left by that body’s absence?

When the mother whose children are yet so very young turns and finds herself face to face with the moment of her death?

When (in a different story) the mother lives and the child lives no longer?

When instead of a baby born squalling through a portal of blood and bone the doorway opens to silence?

When hope is held in both hands over a linoleum floor and a pillow is used to suffocate the sound of sobs?

When the future is buried in a matchbox?

What choices are left to us then?

//

The questions ebb and flow, the anguish ebbs and flows. One day seeps into another until all days are yesterday and tomorrow merged, until all the doors once open to me with her are not merely bolted closed but obliterated…entirely gone.

I hear her laughing up in the garden, but the garden is empty now. Her windchimes hang from a high branch of the mulberry tree across the way and ring clear when the wind blows. If I stand by the firepit or down by the garden I can almost feel their song in the vibration of my bones.

What did she think, in the depths of her soul, when all choices once available to her in her vibrant body and her vivid joy were reduced to no choices at all?

When she could not even open her mouth to speak?

What is it to utter such things over and over when tracing the outline of where a beloved used to occupy the fabric of spacetime? To be human is to be intimately acquainted with endings, and to know that all promises eventually carry away in the wind.

There is no clear answer here, in the boneyard, in end of all decisions.

I am back with her, in that breath of space between her here, spirit tethered for a split second more in flesh, and her gone, in the moment just after her heart stopped, and the words are for both of us:

To let go of our identity—and find out who we are.

To give up our hold on life—and watch existence rush in to greet us.

To accept that there are no choices left—and step into an endless field of possibility.

//

I am not sure yet where I will find her, or what the encountering will be.

But if it comes—when it comes—I will be here for it, eyes wide open. My hands are open. My heart is seeking what is still possible.

I am on my knees, face pressed to the ice-wind of the ages, peering out of a world I recognize into one barely seen but greatly felt.

Time moves and her body is dead.

And still, I am here, searching for where the shadow recedes and the light begins.

Beyond beautiful 🙏🏼♥️😭

I can really feel your heart here ♥️ I cannot fathom the loss of a Mother. Thinking of you and your mama today ♥️